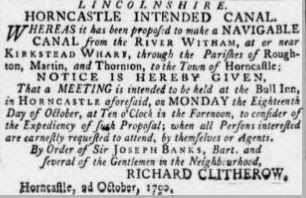

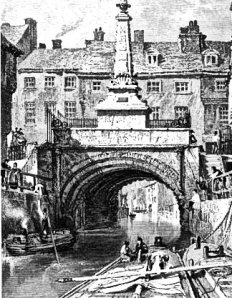

Joseph Banks, painted 1773 by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Sir Joseph Banks is well-known as a naturalist and botanist, the son of William Banks a wealthy Lincolnshire land owner. Joseph was also a farmer and business man and was instrumental in promoting the Horncastle Canal.

An Act of Parliament was passed in 1792 approving the building of the canal; the canal was completed by 1802 but was partially in use some years before this.

In order to make the canal viable it was essential that barges could navigate to and from the Trent: the only route was through Lincoln.

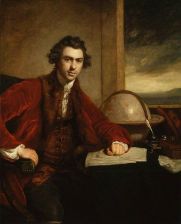

Richard Ellison had acquired a 999 year lease for the Fossdyke Canal and river Witham in 1740, he dredged and improved the canal and the river east of Lincoln but was prevented by Lincoln Corporation from improving the navigation below High Bridge. Lincoln Corporation earned valuable revenue from porterage fees, barges were unloaded one side of the Bridge and reloaded the other. The problem was so severe that in exceptionally dry summers it was possible to drive a coach across the bed of the river west of High Bridge.

High Bridge c 1836

The reluctance of the Corporation to act on the navigation under High Bridge forced Joseph Banks to look at alternative routes. William Jessop, the noted canal builder (locally he built the Grantham and Sleaford canals), was commissioned to investigate a likely route. Jessop put forward a scheme to route barges from the Fossdyke southwards on the upper Witham to Sincil Drain, in effect by-passing Lincoln. The Corporation realised this would be devastating for the economy of the city and, in 1795, the bed of the river beneath High Bridge was lowered at the expense of the proprietors of the Horncastle Canal. To celebrate the event boards were laid on the dry river bed and a dance took place under the bridge.

The building of the Great Northern Railway from Lincoln to Boston in 1848 dramatically increased the traffic on the Horncastle Canal but in 1854 a line was opened from Kirkstead to Horncastle: the canal closed in 1889.