Henry Poppleton was born in Hull in 1829. Within a few months of his birth the family moved to Lincoln, living in Sincil Street. William Poppleton, Henry’s father, was a shoemaker and Henry followed him, as an apprentice, into the trade, but realising it was not for him he worked for Thomas Hibbert at 36 Sincil Street as a baker at a wage of 4/- (20p) per week.

Henry worked for Hibbert for a number of years, eventually running the shop in his own name from about 1850, as a baker and flour dealer, when Hibbert moved to Canwick windmill as a miller. Henry married Thomas Hibbert’s daughter, Elizabeth Sarah, on Christmas Day 1851 at St Swithin’s church.

Henry was appointed secretary of a local bakers organisation in 1855 with the aim “that some uniform understanding should be come to respecting the retail price of flour, in order that something like unity should prevail in our charges to the public”. By 1859 Thomas Hibbert was back running the shop in his name, as a baker and biscuit maker, and Henry moved to 9 Guildhall Street, the Yorkshire Bank now stands here at numbers 8 to 10. He set himself up as a baker at Guildhall Street but soon saw confectionery as a more profitable business.

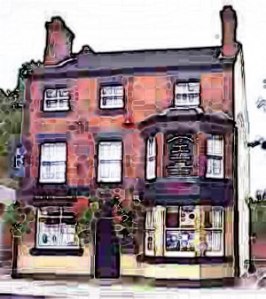

He was a Victorian entrepreneur, seeing the advantages of expanding the range and breadth of products offered in his shop, but this involved another move, this time to 198 High Street; confectionery included cakes and biscuits, bride (wedding?) cakes; pound, sponge and tea cakes; pastry; Rich Mixed Biscuits; Keiller’s marmalade; jams, jellies, Little John’s Rusks. Poppleton’s Butterscotch and Penny Cough packets. Number 198 was in a prominent position opposite the Cornhill and next to the Black Bull Hotel, it was demolished for the building of the British Home Stores department store

His ambitions soon outgrew the High Street shop, and in 1885 he bought premises, behind the shop, at Brayford Head to expand production of his range of sweets, the shop continued as a retail and trade outlet until it came into the possession of Samuel Patton, another confectioner, in the early 1890s. (There is an interesting and tragic post about Samuel Patton on the It's About Lincoln group page, click this link to view http://bit.ly/s-patton

At about the same time a John Chynoweth and Giles Jory Lockwood Lang (brother-in-law of George Poppleton) became partners with Henry Poppleton and his sons, George and Henry William, and company became: Chynoweth, Poppleton & Co. The partners needed land to build a factory and the Ellison family were selling land at the northern part of their estate for industrial development. Their new factory was built on the north side of Beevor Street, New Boultham in the early 1890s, there was a railway line on the south-side of the factory connected to the Midland Railway, giving the factory access to the rest of the UK. The architect was James Whitton and the builder, Crosby and Sons.

The partnership was dissolved in 1901 and the name of the business returned to H Poppleton & Sons. The business was turned into a limited liability company in 1910, becoming Lindum Confectionery Ltd; Henry Poppleton was Chairman, Henry William Poppleton was manager of the works and George and Frederick Lister Poppleton were commercial travellers selling to retail shops.

Henry Poppleton died on 21st September 1912. He was a Free Methodist preacher for over 60 years only retiring a year before his death. Henry and Elizabeth had eight children, four sons and four daughters, of the sons George (1855-1921), Henry William (1861-1932) and Frederick Lister (1869-1927) joined their father in the business, Charles Herbert (1857-1940) was a Methodist minister.

In the 1920s the address of the works became Rich Pasture Works, New Boultham, Lincoln.

The research of the Poppleton's has been very interesting, do you have any photos of the factory, interior and exterior, of the people who worked there? Did you have relations who worked there? I have built a family tree from William Poppleton (1796-1867), Henry's father, are you researching the family? Please contact me via comments at the bottom of the page.