Katherine de Rouet was born in about 1349 in the County of Hainult, now in Belgium, the daughter of a Flemish Herald, Sir Payne de Rouet. She was educated at a convent in Romsey, Hampshire and later joined her sister Philippa, who became the wife of Geoffrey Chaucer.

Katherine married Sir Hugh Swynford of Kettlethorpe and Coleby, Lincolnshire, a knight in John of Gaunt's service, about 1366. Sir Hugh died in 1371 in Gironde, Bordeaux. Katherine and John of Gaunt began their relationship sometime after Hugh's death.

John of Gaunt, the 3rd son of King Edward III was born in Ghent in 1340. He married his first wife, Blanche of Lancaster, his third cousin, in 1359. Blanche died of bubonic plague in 1368 at Bolingbroke castle.

After the death of John's first wife, Katherine became the lady-in-waiting to Blanche's daughters. She took care of them and managed the estates left to her by her late husband.

John married Infanta Constanza of Castile in 1371 at Roquefort near Bordeaux, assuming the title “King of Spain” in 1372. In 1387 he tried, with the aid of King Joao I of Portugal, to conqueror Castile to make good his claim, but was unsuccessful.

During John of Gaunt’s marriage to Constanza he fathered four children by Katherine Swynford.

Their relationship caused a scandal, leading to John being forced to break off their relationship in 1381. Katherine moved to Lincoln and lived in a rented house.

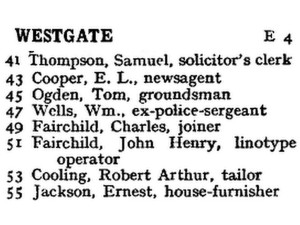

|

The Chancery, Katherine's rented house |

Despite the formal separation, Katherine maintained a cordial relationship with John and his family. In 1387, she was made a Lady of the Garter by King Richard II

Constanza died in 1394.

John married Katherine Swynford in Lincoln Cathedral in 1396/7. Their marriage was recognized by a papal bull, legitimising their children, taking the surname of Beaufort, but were prevented from inheriting the throne. The children were:

- John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset (1373-1410)

- Henry Beaufort, Cardinal (c. 1374-1447)

- Thomas Beaufort, 1st Duke of Exeter (1377-1426)

- Joan Beaufort, Countess of Westmorland. (1379-1440)

Henry Beaufort was bishop of Lincoln from 1398 to 1405 and was created Cardinal in 1426.

Although John of Gaunt didn’t inherit the English throne all sovereigns of England and Great Britain from Henry IV are his descendants.

John of Gaunt died in 1399, his estates were declared forfeit by King Richard II as John’s son and heir, Henry Bolingbroke, had been exiled.

Henry returned to England to depose Richard and reigned as King Henry IV until 1413.

Katherine died on 10th May 1403 and is buried in Lincoln Cathedral.

|

| Katherine Swynford's Tomb in Lincoln Cathedral |

Katherine's children with John of Gaunt played significant roles in English history. Their descendants include Henry VII, the first Tudor king, and key figures in the Wars of the Roses