Lincoln was one of the last major towns or cities to be linked by rail, a line from London to Cambridge had been proposed in 1825 and would have extended to York via Lincoln, this route was abandoned. In the event, the London to York line followed a route to the west of the River Trent mainly due to the lobbying of Doncaster’s MP, who believed that a line running through Lincoln would be detrimental to his town.

Railway promoters became active again in 1833 when three routes were proposed through Lincoln. In March 1835 a Lincoln committee under the chairmanship of Thomas Norton, the City’s mayor, reported on the alternative routes. Again, nothing came of this move to bring the railway to Lincoln.

In 1845 a meeting of 6,000 people at the Beast Market ended in a free fight when the chairman, the Lincoln mayor, announced that the London to York line had won the right to serve Lincoln. Opponents complained that labourers had been brought at 2/- (10p) a piece to vote for the London to York project. George Hudson, “The Railway King“, had spent a lot of money opposing the line in favour of his Midland Railway. His boast was that he would bring a railway to Lincolnshire while the rest were still talking about it!

Hudson’s boast came true when the Midland Railway brought the first route into Lincoln from Nottingham. The line opened on 3rd August 1846, the first train left Nottingham at 9 am, stopping off at the various villages en route to pick up those invited to celebrate the new enterprise, and arriving at Lincoln at 11 am.

It was an important day for the city: the buildings and streets were decorated, the bells of the Cathedral and churches ringing peals at intervals, the band of the 4th Irish Dragoons played the “Railway Waltz” as two trains left the Midland Station, carrying local dignitaries and cannon were fired. The journey to Nottingham took almost 2 hours. The return journey was in heavy rain. A banquet was held in the National School in Silver Street.

Unfortunately there was a casualty of all the merriment: a man called Paul Harden has his leg shattered by the bursting of a cannon in the station yard. He was taken to the County Hospital where his leg was amputated.

The Great Northern Railway opened in 1848, this line was routed from Peterborough through rural Lincolnshire, via Sleaford. Lincoln now had two railways crossing the High Street. The town clerk was sent to London to enquire whether both lines could be routed through one crossing, but he was assured that the crossings would not have a detrimental affect on the flow of the road traffic using the High Street.

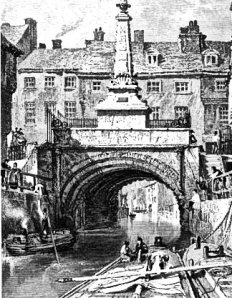

|

The Elegant Entrance Portico of the Midland Railway Station,

now part of St Mark's Shopping Centre |

The coming of the railways completely transformed Lincoln’s communications with other parts of the country. The produce of Lincolnshire’s farms and factories could be easily transported and in return coal for homes and industry could be brought into the county. Travelling by mail coach to London took 13 hours whereas by train it would take a mere 4 hours: a businessman could leave Lincoln early in the morning transact his business in London and return home in the evening to sleep in his own bed. In less than 5 years railway lines radiated from Lincoln in all directions.

Prince Albert passed through Lincoln in 1849 to lay the foundation stone of the Grimsby docks.

On the 27th August 1851 Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and the Prince of Wales had a brief stop at Lincoln, en route for Balmoral. An address was read by the Mayor and he presented the keys of the city, following Her Majesty’s reply some grapes That had been grown by Richard Ellison of Sudbrooke Holm. The Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, was a regular visitor to the city by train, mainly for the horse racing, as a guest of Henry Chaplin of Blankney Hall.

The Midland Station, otherwise known as St Mark’s Station, closed 11 May 1985, the Great Northern Station, now known as the Central Station continues to operate from St Mary’s Street.

First published on Wordpress 10th October 2013

The building on the right of Eastgate is The White Hart Hotel, a former coaching inn dating from the 14th century. On the left of the junction was an ancient inn, the Angel; a gate to the Cathedral Close stood at this junction between the White Hart and the Angel. The Angel Yard remains behind the Post Office.

The building on the right of Eastgate is The White Hart Hotel, a former coaching inn dating from the 14th century. On the left of the junction was an ancient inn, the Angel; a gate to the Cathedral Close stood at this junction between the White Hart and the Angel. The Angel Yard remains behind the Post Office.