West Willoughby Hall was was originally built in 18th century in Queen Anne style architecture. The Rev Charles Wager Allix (1749-1795) bought the West Willoughby Estate in the final years of the 18th century.

The Rev Allix was coursing (chasing a hare on horseback with dogs) with his servant. He decided there was time for a ride before dinner. When they were about a mile from home he started to fall from his horse, his servant caught him and laid him on the ground. The servant let his horse loose so it could return to the house and his family would know he was in trouble. At the house no one knew where they were and, eventually the servant left the Rev Allix "senseless and speechless on the ground" and headed to the house on his master's horse to inform the family and bring assistance, then he returned to his master. The horse smelled the Rex Allix snorted, ran back a few steps, fell on his side and died in less than two hours. Rev Allix remained unconscious for a week when he passed away.

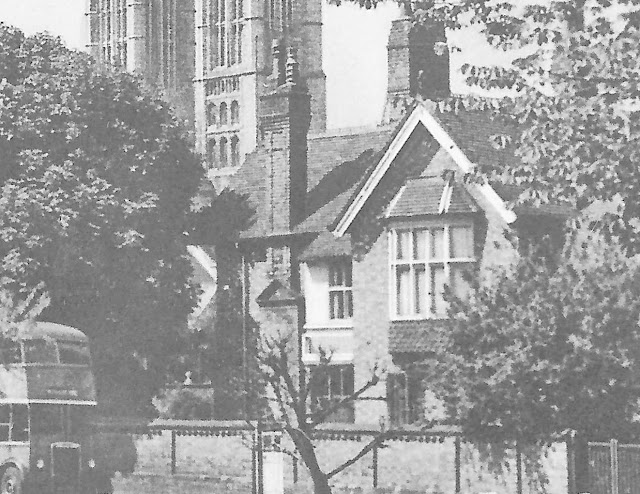

His son, Charles Allix (1783-1866) developed the farming potential of the estate. Charles' son, Frederick William Allix, employed Lincoln architect William Watkins to design a new house in place of the original hall. The new Hall was built in 1873 at a cost of £28,000 using local Ancaster stone.

It was large and, like most of Watkins' work, elaborate and expansive. Jacobean in style and similar to Dutch and French Renaissance styles. For all its granduer the house was unloved by the Allix family and often tenanted, F W Allix and his wife spent most of their time living in Brussells

F W Allix died in 1894, his wife, Mary Sophia, died in Brussels in 1910.

In 1912 the estate was auctioned to several buyers, except for the house and park. The house was rented then bought by the Rev. H.W.Hitchcock, acting as agent for his eldest brother.

Practically all of the West Willoughby Estate was sold off in fourteen lots

The house was auctioned in 1928 but withdrawn at £2,750.

The house remained empty until World War II when it was occupied by the army, the Hall was badly damaged and even used for target practice.

It lingered on in ruinous state until 1963 when dynamite was used to demolish it. All that remains is a stable block with a datestone of 1876.

The stable block has been renovated and is now (2010) converted to a family home. The extensive grounds have been incorporated as the lawns of the dwelling. The foundations of West Willoughby Hall have been observed by the current occupier (2010) of the stable block during landscaping work that has taken place over the past eleven years. The foundations lie approximately 50 metres to the south-east of the stables. Some former lodges to the hall remain but have been in private ownership for at least thirty years. The front (south) elevation has had an entrance door added beneath a new central Dutch gable which complements the original two. At the rear, large wooden entrance doors have been added to enclose what was previously an open arch, linking the front of the stable building with the rear. {5}"In 1959 I described Willoughby Hall near Ancaster, Lincolnshire as ‘a tall, gaunt, French-style house of 1873, said to be by Watkins and in ruins’; in 1989 my text was revised to read, “Of the French-style house of 1873 by William Watkins only the stable block of 1876, with shaped gables, remains.’ Today I would further revise my stylistic judgement: I believe Willoughby was a very clever adaptation from local seventeenth-century Northamptonshire and south Lincolnshire models, and that it had also benefited from the Flemish taste of Frederick Allix’s wife Sophia. At the time he was working at Willoughby, Watkins had already built in 1867 the Town Hall at nearby Grantham.

"I had come to Willoughby in the late afternoon from Caythorpe, its walled park and funerary monuments so redolent of the Hussey tenure. Being Lincolnshire, this was RAF country, the domain of ‘Bomber’ Harris. My index card said ‘Mucked up by the RAF — from Cranwell’, but the army were billeted here too. I was puzzled by large numbers at least two feet high painted on the roof and thought of demolition, but learned later that the RAF used the numbers to practise precision bombing in their Mosquitoes. Even from a distance, a spookiness seemed to emanate from the ruin as I approached, a feeling not unlike that which I'd experienced at Bulwell in Nottinghamshire. I knew nothing then of Charles Hitchcock, a lunatic who, cared for by his brother the Reverend Harry, was incarcerated here from 1912 until his death in 1928. It is said that he would appear with a handkerchief on his head, and run away when approached. Another tale is attested to by old Mr Simkins, the Hitchcocks’ gardener. He reported that Charley had the run of the attic floor, and was allowed out into the garden at three o’clock each afternoon, superintended by a maid. Simkins could point to the gabled window on the garden front from which Charley would sing to and stare at the moon — it seems that he would get into a frightful state if there was no moon on a night when he needed its consolation. One such night, he ran up and down the stairs so many times that he finally collapsed exhausted at the bottom. Simkins also claimed that Charley had a passion for Mars bars, which his brother used to supply in bulk. This surprised me, and later enquiries made to the Mars bars people in Slough revealed that the bars had only been marketed from 1932. Maybe Charley’s ghost consumed them? The house was untenanted after Charley’s death in 1928. When the army moved in, a carved French chimney-piece was there one day and gone the next, and according to Simkins, no doubt a local myth-maker, the house was badly haunted. Objects would suddenly break, as if someone had smashed them. ‘A real nasty feeling the place gave,’ he confessed. There were noises in the night, but it was not clear if these were the gasps of soldiers in the embrace of WRACs, or Charley's ghost moaning at the moon.

"Looking back, I don’t believe I have never found a ruin so unpleasant. The back parts had been used as pigsties, and stank from the inevitable muck-heap. In the stables the walls were plastered with army notices. Each stall had housed not horses but soldiers, eating around a table, and the columnar divisions had all been broken up for firewood, as had the balusters of the upper main staircase and the panelling in the dining room. Upstairs, only accessible by sidling along a wall beam over a precipitous drop, the wet rot bulged out of walls like balloons, and the stench of decay was choking. I’m sure Charley had been harmless, but he left a legacy of evil emanations. I felt cold, on this warm summer’s evening"