Lincoln's Caroline Martyn - "the leading socialist of her day"

The History of the Usher Gallery & Temple Gardens

Temple Gardens

Temple Gardens is in one of the most historic parts of the City. On the eastern side of the Gardens is a Roman defensive ditch, and on the western side once stood the Roman wall and rampart of the lower city. In the northern part of the Gardens is the site of St Andrew's-under-Palace church, established during the 11th century; it was one of the 40 Lincoln churches pulled down in the early 16th century.

Joseph Moore, a Lincoln solicitor, named the area Temple Gardens and opened it to visitors  for an annual fee of 10s. (50p), payable in April of every year, in 1824 as a pleasure ground. The Gardens were laid out with plants and antiquities. Moore had built a copy of the Greek Choragic Monument of Thrasyllus. Band concerts and exhibitions were held in the Gardens.

for an annual fee of 10s. (50p), payable in April of every year, in 1824 as a pleasure ground. The Gardens were laid out with plants and antiquities. Moore had built a copy of the Greek Choragic Monument of Thrasyllus. Band concerts and exhibitions were held in the Gardens.

The second annual "Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire Grand Brass Band Contest and Peoples Festival" was held on 6 June 1859 at Temple Gardens, total prize money was £50. Sixteen bands had entered and the public could attend on the payment of 1 shilling (5p) the event ended with a "grand display of fireworks. Cheap train tickets were made available throughout the area covered by the contest.

Band concerts and fetes were regular attractions at Temple Gardens.Joseph Moore died on 21st May 1863, and the Gardens were closed. The plants and equipment were sold at auction by Brogden & Co on 4th April 1864.

The Gardens were left to become overgrown, and were eventually bought by the Collingham family of Mawer & Collingham, the Lincoln department store on the corner of High Street and Mint Street, and added to their house at 7 Lindum Road. The house and Temple Gardens were sold in the early 1920s to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners.

|

| 7 Lindum Road, the Collingham family home |

Usher Gallery

|

The Usher Art Gallery (as it was once known) came about due to a bequest from James Ward Usher, a Lincoln jeweller. James was an avid collector of ceramics, watches, clocks, coins, silver, miniatures, and paintings.

James never married and left his collection to the City of Lincoln together with almost £60,000 (equivalent to £3,447,000.00 based on the retail price index) to design and erect a suitable building to house it.

The Ecclesiastical Commissioners imposed certain conditions when the land was sold to Lincoln Corporation; one of these conditions was that the building should stand in the north western corner of Temple Gardens; eventually it was agreed that the Gallery should be built on the tennis courts where it now stands. Sir Reginald Blomfield was commissioned to design the building; he also designed the Central Library and Westgate Water Tower, and William Wright and Son (Lincoln) Ltd. were engaged to erect the building, which began in August 1925. Two foundation stones were laid on 10th March 1926, by the Mayor of Lincoln, Councillor Miss M E Neville, the stones were left plain at the request of Miss Neville. A total of 119 piles from 14 to 25 feet long were used to stabilise the ground. The cost of the building was in the region of £34,000.

The Gallery was officially opened on the 25th May 1927 by the then Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) with a solid gold key.

The Collection archaeology museum is located on Danes Terrace near to the Usher Gallery, visit the Collection website: https://www.thecollectionmuseum.com/

Lincoln's Rarest Gem

Lincoln Companies - H Newsum & Sons Ltd

Newsum's Villa

Newsum Villas were built in 1920 on the northern perimeter of Newsum's new joinery works. One detached and eight 3 bedroom semi-detached houses were built for senior staff at the works.Designed in a pseudo-Georgian style, the houses are well built in brick and well proportioned. Sadly all the houses except one have had their Georgian proportioned sash windows replaced with upvc double-glazed units that detract from the design of the houses. The house in the photograph was in the process of being renovated when I photographed it and has had its beautiful wooden windows replaced.

Lincoln's Reformation

An application was made to Parliament for the purpose of uniting the parishes, and an act was passed by in 1538, "for the union of churches in the City of Lincoln", authorising four people to carry it into effect, they were: John Taylor, the bishop of Lincoln; William Hutchinson, the mayor; George Stamp and John Fowler.

A copy of the deed of union, dated 4th September 1553, states that the parishes in the City, Bail and Close of Lincoln were reduced from fifty two to fifteen. One of the doomed churches was St Andrew's which stood on the junction of the High Street and the street now known as Gaunt Street.

St.Andrew's Church stood behind the wall in the centre of the picture. The graveyard remained there until West (of West's garage) built his house and shops on the site in the late 19th century.

The Sutton family lived in the large house that was known as "John O' Gaunts Palace" and petitioned the City Corporation not to demolish the church. The Sutton's annexed St Andrew's Church as their own private chapel and would have kept it at their own cost. The timber, the lead, the glass, and the stones were too valuable and Lincoln Corporation was set on a course they would not be deterred from taking. The church was pulled down in 1551, some of it was used in the repair of the remaining 15 churches.

Lincoln's fortunes wouldn't improve for another 300 years with the coming of the industries created by such men as Ruston, Clayton, Shuttleworth, Foster and others.

|

| West's building on St Andrew's Graveyard 1885 map of the area |

Lincoln Companies - Lincoln Gas, Light and Coke Co.

History

Other Suppliers

It wasn't viable for the company to lay pipes outside of Lincoln, companies like Porter & Co of Lincoln, supplied complete gas plants to large country houses and some villages so that gas could be produced locally. Hartsholme Hall had its own gas plant, probably supplied by Porters.

Bracebridge Gasworks

The owners of the gasworks had tried for several years to sell it. In 1885 agreement was made with Lincoln Corporation to buy the gasworks.

1885 Statistics

163,000,000 cubic feet produced

5,789 consumers

Main 35 miles long

The Cost of Gas in 1913 was 2/- (10p) per 1,000 cubic feet

Helping the War Effort

During the First World War a by-product recovery plant was installed to extract Toluol and Benzol for the high-explosive industries

Showroom

First showroom opened in 1919, later moving to Silver Street.

1933 Statistics

Wages £25,996, 102 miles of mains, 17,796 consumers, 1,884 street lamps, 12,242 gas cookers, 33,257 tons of coal carbonised, 14,014 gallons of oil used, 21,617 coke made, 412,275 gallons of tar, 324 tons of sulphate of ammonia, 560,000,000 cubic feet of gas produced an increase of about 25% over the previous 10 years

A New Gasholder

The rapid increase in consumers during the previous 40 years meant that the maximum storage for gas was only enough for 12 hours consumption.

Various types of gasholder were inspected and in 1930 a new holder of the three-lift spiral guided type was ordered to increase storage capacity. The capacity of the new holder was 1,500,000 cubic feet.

The End of Coal Gas

Natural Gas was found in 1910 in Germany, in the mid-1950s BP discovered natural gas fiels in several places in the UK, a field was discover near Gainsborough in the late 1950s. It wasn't until the 1970s that drilling for natural gas in the North Sea became economically viable due to the 1973 oil crisis. Since that time coal gas production has ceased in the UK.

The Virgin Mary and the Wain Well

|

| Eastgate from Bailgate |

The building on the right of Eastgate is The White Hart Hotel, a former coaching inn dating from the 14th century. On the left of the junction was an ancient inn, the Angel; a gate to the Cathedral Close stood at this junction between the White Hart and the Angel. The Angel Yard remains behind the Post Office.

The building on the right of Eastgate is The White Hart Hotel, a former coaching inn dating from the 14th century. On the left of the junction was an ancient inn, the Angel; a gate to the Cathedral Close stood at this junction between the White Hart and the Angel. The Angel Yard remains behind the Post Office.

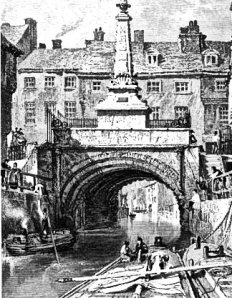

Banks and High Bridge

By Mail Coach to London

|

| "Royal Mail" coach operated from the Reindeer and the Saracens Head. |

|

| 1828 Pigot & Co Directory |

People made their wills before they were "received into the York stage-coach, which performed the journey to London (if God permitted) in four days."

|

| Denbigh Hall bridge which took the railway over Watling Street |

Denbigh Hall Station closed in November 1838 when the railway continued north west to Birmingham.

|

| Travelling by coach wasn't always plain sailing, Lincolnshire Chronicle 13 July 1838 |

The demise of long distance coach travel had a retrograde effect on taverns and inns, in particular the hamlet of Spital-in-the-Street where the number of coaches supported two inns.

The Schoolboy who Killed a King

|

| John Hutchinson |

|

| Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Norfolk |

In October 1663 Hutchinson was arrested on suspicion of being concerned in what was known as the Farnley Wood Plot. Hutchinson was to be transported to the Isle Man, but instead was sent to Sandown Castle in Kent in May 1664, he died of a fever there on 11 September 1664, aged 49.

He was buried at St Margaret's Church, Owthorpe, Nottinghamshire.

Lincoln's Industrial Revolution

Lincoln was about to go through immense change, Richard Ellison had purchased a 999 year lease on the Fosdyke Canal in 1740 and set about improving navigation on the canal and the river Witham east of Lincoln. Farm produce and others goods could be sent from Lincoln by barge to other parts of the country and coal and lime could be brought in. Lincoln, surrounded by agriculture, was late in embracing the Industrial Revolution.

It was the 1840s when the Industrial Revolution arrived in Lincoln. These people made a massive contribution to the growth of prosperity of Lincoln, click on the links to learn about their companies

William Rainforth

Nathaniel Clayton and Joseph Shuttleworth

Richard Duckering

Robert Robey

William Foster

Joseph Ruston

John Cooke

|

| Lincoln's Waterside Industrial Area Today |

Lincoln was one of the last major centres of population in England connected to the railway, the Midland Railway arrived in Lincoln in 1846 and the Great Northern in 1848, bringing with them traffic delays on Lincoln’s High Street.

In the period 1841 to 1861 Lincoln’s population grew by over 50% to almost 21,000, the population of St Swithin’s and St Peter at Gowts parishes, where most of the engineering firms were based, almost doubled. At the end of the 19th century the population of Lincoln was 48,784 more than three times that of Boston.

|

| Clayton & Shuttleworth's Iron Works in 1869 |

The Decline and Rise of Lincoln

|

Arms of the city of Lincoln

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)

|

Counties Corporate were created during the Middle Ages, and were effectively small self-governing counties of no prescribed size but usually including some surrounding countryside and villages. They usually covered towns or cities which were deemed to be important enough to be independent from their county. Each town or city’s charter was drafted according to its needs, in some cases there was a security issue which brought about the status, i.e. Poole was plagued by pirates so became County of the Town of Poole.

|

| Lincoln's Stonebow, Meetings of the Corporation/Council have been held here for five centuries |

While they were administratively distinct counties, with their own sheriffs, most of the counties corporate remained part of the “county at large” for purposes such as the county assize courts. From the 17th century the separate jurisdictions of the counties corporate were increasingly merged with that of the surrounding county, so that by the late 19th century the title was mostly a ceremonial one.

Lincoln’s County Corporate status was made by a Royal Charter dated 21st November 1409. The main points of the charter were:

- The election of two sheriffs instead of bailiffs.

- The city to be called the County and City of Lincoln.

- The Mayor to be the King’s Escheator¹.

- The power to render accounts to the King’s Exchequer by attorney.

- The Mayor and Sheriffs with four others to be justices of the peace, with defined jurisdiction.

- A yearly fair beginning fifteen days before the feast of the deposition of St. Hugh (17 November) and continuing for fifteen days after.

- The receipt in aid of the payment of the city rent of £180 of the annual rent of £6 paid to the Crown by the weavers of Lincoln; strictly and fully reserving the exemption from the jurisdiction of the City of the Cathedral Church, the Close, and the Dean and Chapter.

The Charter was witnessed at Westminster by the archbishops of Canterbury and York, the bishops of London, Durham, and Bath and Wells, Edward duke of York, John earl of Somerset, chamberlain, John Typtot, treasurer, master John Prophete keeper of the Privy Seal, and John Stanley, steward of the household..

By the 15th century Lincoln’s fortunes were on the wane, it’s Jewish community, the second largest in he country after London, had been expelled 100 years before and in 1369 the Wool Staple² was moved to Boston: the population of Lincoln had fallen to its lowest level because of these reasons and the Black Death which ravaged most of England at this time. Buildings were demolished and the land was turned back to farming, even within the city walls. Lincoln’s population at this time was in the region of about 2,000, drastically down from its 6,000 at the time of the Conquest. Many churches were closed, some were demolished, there being parishes that were uninhabited.

Lincoln started to revive in the 18th century due to many factors, the main one being Richard Ellisons leasing and making navigable again the Fosdyke. The population grew and at the 1801 census there were over 7,200 people in Lincoln, and by 1901 the population had grown to nearly 49,000. The Industrial Revolution had arrived!

In 1466 a Charter was granted by Edward IV “to the Mayor Thomas Grantham and the citizens, in relief of the desolation and ruin which had come upon the city, that the villages of Braunstone, Wadyugtone, Bracebrigge and Canwik should be separated from the county and annexed to the county of the city, with the transfer of all jurisdiction of sheriffs etc., that all their inhabitants should contribute to "scot and lot" and all the charges of the city, and none be allowed to dwell within the liberties of the city who should refuse so to do… “

County Corporates were abolished through Government Acts in the 19th century, notably the Militia Act 1882 and Local Government Act 1888, Lincoln becoming part of Lincolnshire County Council but retaining it’s City Council status.

The list of Counties Corporate and when created

1. County of the City of …

- Canterbury (1471)

- Coventry (1451, abolished 1842)

- Exeter (1537)

- Lichfield (1556)

- Lincoln (1409)

- London (1132 until 1965)

- Norwich (1404)

- Worcestor (1622)

- York (1396)

2. County of the Town of

- Bristol (1373, City since 1542)

- Chester (1238/1239, City since 1541)

- Gloucester (1483, City since 1541)

- Newcastle upon Tyne (1400)

- Nottingham (1448)

- Poole (1571)

- Southampton (1447)

3. Borough and Town of …

- Berwick upon Tweed (1551)

1 A person appointed to receive property of a person who died intestate.

2 Lincoln was originally granted the Wool Staple in 1313 due to the importance of its Cloth industry, its loss was a blow the Lincoln didn’t recover from for a very long time.

First published on Wordpress 1st May 2013

Click here to read the next part of this story

What’s this Lincolnshire Stuff?

Posted on August 10, 2013

|

| Lincolnshire Longwool Sheep |

The Bridge of Sighs

The original bridge was eventually replaced in 1958, this bridge was replaced in 1991 and again in 2001.

The 1869 bridge and the 1958 bridge shortly before the removal of the earlier bridge. Note the wooden planks used to support the side of the 1869 bridge.

The 1958 Bridge

What of James Mayfield? James sold his boot and shoe business to Thomas Mawby in 1874 and became licensee of the Globe Inn on Waterside South, moving to Edmonton, London in 1881 to open a boot and shoe shop; he died there in 1887.

It's About Lincoln has its own groups on Facebook where you can read about the city and county, and contribute to the growing knowledge of our members or just read the posts.

The Lincolnshire group can be found at: